The Lower Road 1948-1964 by Mrs. Catherine Moran (nee Rea) c2005

In the early 1900’s the ‘Spillane’ family ran a grocers shop at 116 Lower Road, and they lived over the shop. They were a large family. Some of them went to America. In the time of the troubles it would have been known as a safe house.During the 1914-18 war one of the sons built an ‘air-raid shelter’ in the garden. The eldest of the family was Nell. she lived all her life at 116. She was a single lady. A brother of hers fell out of the bedroom window on the second floor, due to his severe head injuries he had to have a plate fitted in his head.

He spent a few years in America but had to return as the heat effected his head. When the Spillane family retired from the grocery business, sometime in the 1940’s the premises became a ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’s hairdressers shop.

It was run by Billy Donovan and he employed my father David Rea. The men’s hair was cut in the front room while the room behind was for the ladies. Here ladies had their hair cut, permed and dyed and even wigs were made on the premises. Billy and Dave worked very long hours particularly at the weekends. Billy Donovan and his wife Johanna lived at ‘Clehane Cottages’. They had two children, Richard and Margaret. After Billy’s death Dave ran the business on his own and the ladies side of the business ceased. David and Margaret Rea and their two children came to live at 117 Lower Road around 1946. While living on the Lower Road, John, Anne and Michael were born. So in the mid 1950s the family moved into 116. It was then that I got to know Nell Spillane, at this stage she was old and frail. After school, I would make her tea and get the grocery times for her.

Billy Donovan and his wife Johanna lived at ‘Clehane Cottages’. They had two children, Richard and Margaret. After Billy’s death Dave ran the business on his own and the ladies side of the business ceased. David and Margaret Rea and their two children came to live at 117 Lower Road around 1946. While living on the Lower Road, John, Anne and Michael were born. So in the mid 1950s the family moved into 116. It was then that I got to know Nell Spillane, at this stage she was old and frail. After school, I would make her tea and get the grocery times for her.

She was an eccentric lady and got what she wanted simply because no one would cross her. She got her daily itmes in ‘Neiland’s’ post office. She liked a special loaf called ‘Milk Loaf’. One day I was sent to collect this ‘Milk loaf’ the shop keeper forgot to put the bread away for her but did not leave themselves short, and I was given a different type of bread.

Well Nell was furious. She threw a coat around her shoulders and to a quick time step she marched into the shop and obviously gave a piece of her mind to them and arrived back home with a milk loaf. Friday was pension day, Nell’s treat of the week was a half ounce of snuff purchased from ‘Joe Manning’.

Nell had a fear of hospitals, so my mother looked after her until her death in October 1956.

It was the norm to support one shop, one did not walk out of one and into the next. There were many grocery shops on the road, and each was able to make a living. We had McCoys, famous for a good bargain in ice-cream, Tom Coughlan had a butchers shop near Bassett’s Lane, The Co-Op, Caseys, Linehans for sweets, a vegetable store next door, further on the Post Office, also known as Murays/Neilands, Twomeys ran by two sisters Miss Twomey and Mrs. Mac until they retired in the mid 1950s.

Mrs. Mac never smiled but had a wicked sense of humour. One day she gave the messenger boy a half crown to take the cat to the animals home. Everyhing was fine, until a week later, when he arrived into work one morning, Mrs. Mac was waiting for him with her fore finger crooked, indicating he should follow her out into the backyard, and there was the cat sittign on the wall. She wanted no explanations, just take the cat to the Animal’s home. The messenger boy made sure the cat stayed at the bottom of the Lee on the second trip.

For a short while a Mr. McGregor had a place and it was then sold to ‘George Jackson’. George was a very nice man, and we can thank him for bringing his niece Patsy Meaney to us. Patsy stayed for the long haul, got married to Tim Crowley and reared her family on the Lower Road. We also got to know her parents and sister Mary. Now to continue with the shops, next door but one, we had ‘Mannings’ grocery shop, then the butcher Michael Ryan and his wife Kathleen. Around this time, just around the corner and up the lane we had the shoemaker Mr. O’Keeffe.

The newsagents ran by the Dunnes and later continued by Ms. O’Callaghan. Further down there was Eddie Stanley for vegetables and his brother had a little shop too. Eddie was also a Peace Commissioner and lastly Roycrofts.

All these shops were above the bridge. There were oodles of pubs and a billard room. Kate and Danny Meaney lived at 118. At one time they sold coal, I don’t remember that, but their next venture was ‘pigs’ which were fed onthe left overs or ‘slops’ gathered from the neighbours, an early form of recycling. I can remember the squealing animals being taken away for slaughter.

I think most of my generation will remember ‘Nellie’ (Beattie/Kerins) for the comics. The childen of the area brought their comics to Nellie, and she in turn gave out on loan someone else’s comic and thus I believe she ran the first swop shop in Cork.

Those comics were the bane of my mother – she called them ‘penny dreadfuls’ because we did not do our school homework if comics were at hand. Nellie and her husband John Kerins bred Alsatian dogs. The main guesthouse was “Herlihy’s” known as ‘Cheney House’ because of the shinning tiles that surrounded the door.

The Lower Road was a hive of industry in the 1950s and most of the employment was given by the Harbour Commissioners, C.I.E. known as ‘The Railway’, Barry’s Timber and in later years The Dockyard. Most of the workers travelled to work either on bicycle or walked. In those years, the live cattle for export were driven down the Lower Road and up Water Street to be loaded onto ships or ‘cattle boats’ as they were called locally. I believe one time a bull went beserk because somehow acid got into his eye. That unfortunate incident made the residents on the road nervous, when a herd of cattle appeared on the scene and children were called closer to their front door.

The milk was delievered daily to most houses by Dan Jervois. The customer came to the door with a jug to receive the milk, be it 1/2 or pint plus a tilly. (Note: We think a ’tilly’ was an extra sup added for the cat and not anything to do with an oil lamp!)

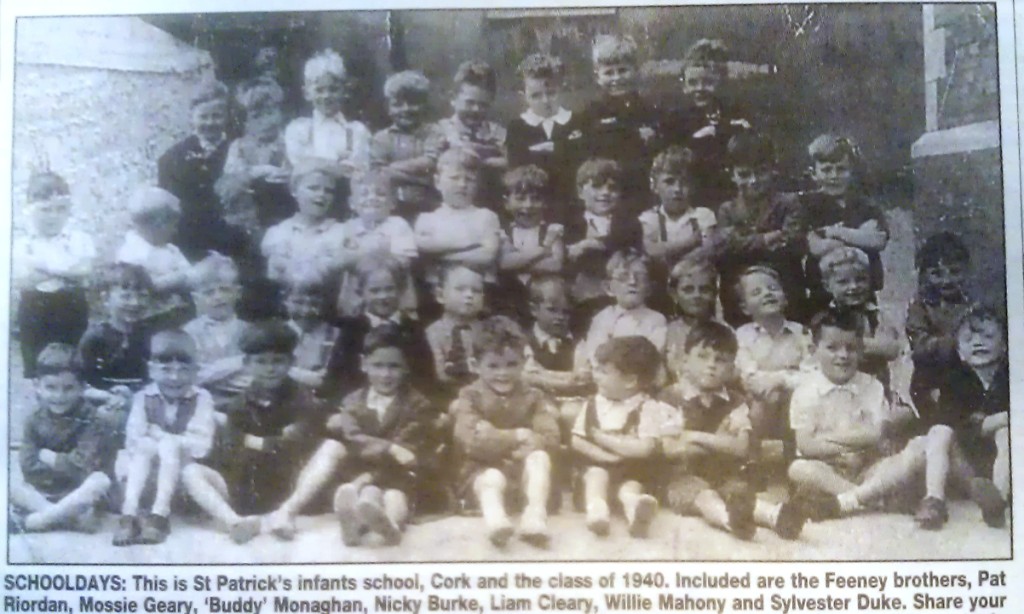

The majority of the children on the road went to St. Patrick’s School N.S. at St. Luke’s Cross. We all walked both ways twice a day in all elements of weather. Most of us children played on the road. We had games for the girls, pickie, skipping, throwing two balls againstt he wall to some rhyme or other, spinning tops, scraps and of course dolls & prams.

The boys played hurling and football, mostly in the old railway line up Grattan Hill. One had to be able to climb onto the wall, and jump down, this kept the smaller boys out. The chestneu season brought ‘chessies’ and then marbles and glass alleys.

The fashion was practical and sensible. In Summer cotton dresses, rubber dollys while the boys had short pants and dollys. In Winter we all had good warm coats with socks to the knee and sturdy shoes plus wellington boots.

I can also remember the bread from the bakeries arriving by a horse drawn van, another occasion I was fascinated by the black carriage with windows and the black horses with their bridles polished and looking very elegant. I did not understand death or why the relatives of the deceased were so demur and silent.

The chocolate crumb was a delightful era, while the bags of crumb were being discharged fromthe ship, occasionally a bag would break. In Winter time, most children wore berets, se we would throw the beret/hat down to the docker and in turn we’d get a quantity of chocolate crumb. This could be chewed, but it was nicer when made into a drink with boiling water and sugar to taste.

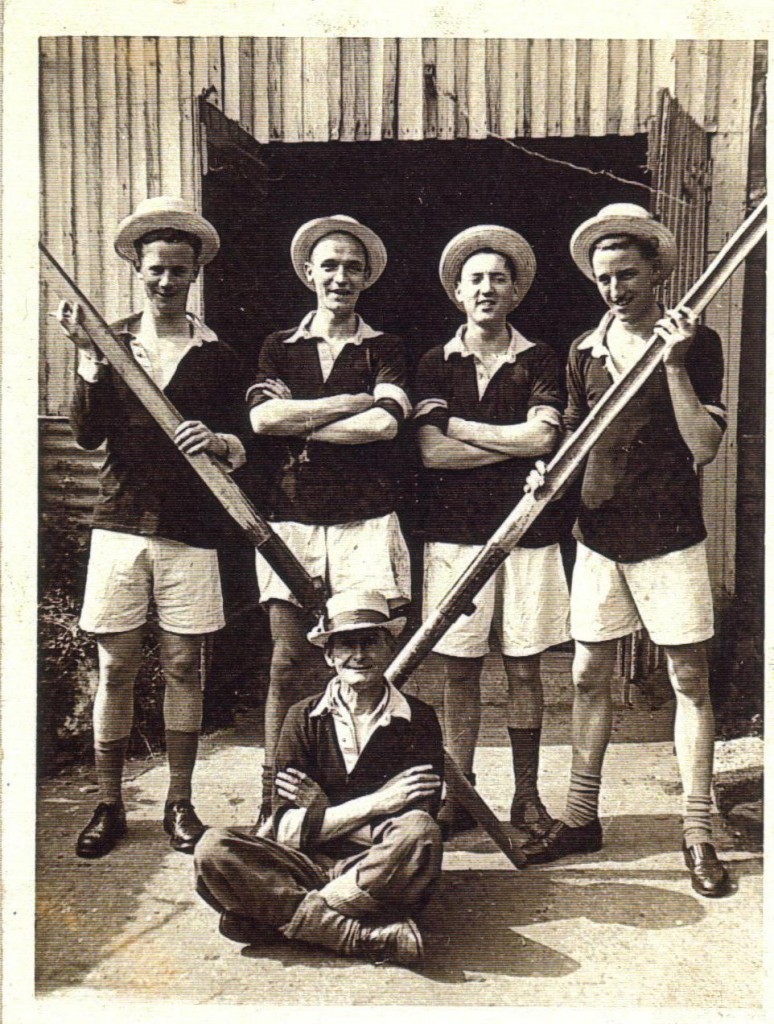

One must not forget the famous ‘Garrett’ family for their manning of the small boats across the river to the various functions on the ‘Marina’ side of the Lee. The hurling/football matches would be scheduled for 3 O’Clock start and the ‘Garrett’s’ rowed hundreds across the river and back again when the match was over. The annual regatta was another busy day on the Lower Road.

That was the life style in those years. All of us youngsters grew up and went into various jobs until one moved on or got married in the case of the girls. My father Dave Rea died unexpectantly in May of 1971 and that was the end of the barbers shop. I left ‘The Road’ in 1968 to do a bit of travelling in Europe and then settled in London for a few years.

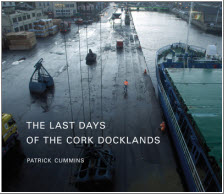

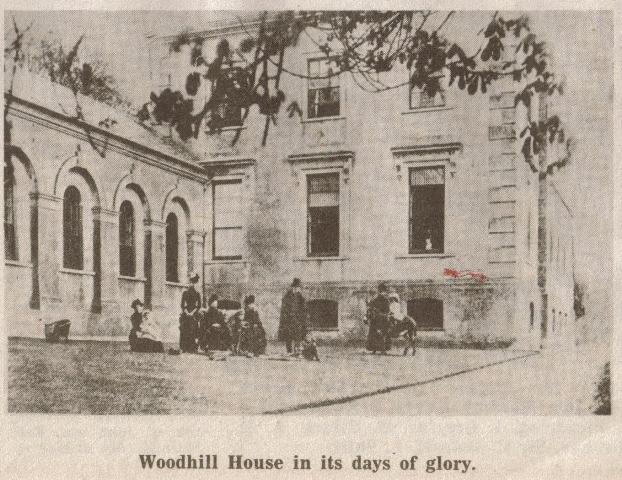

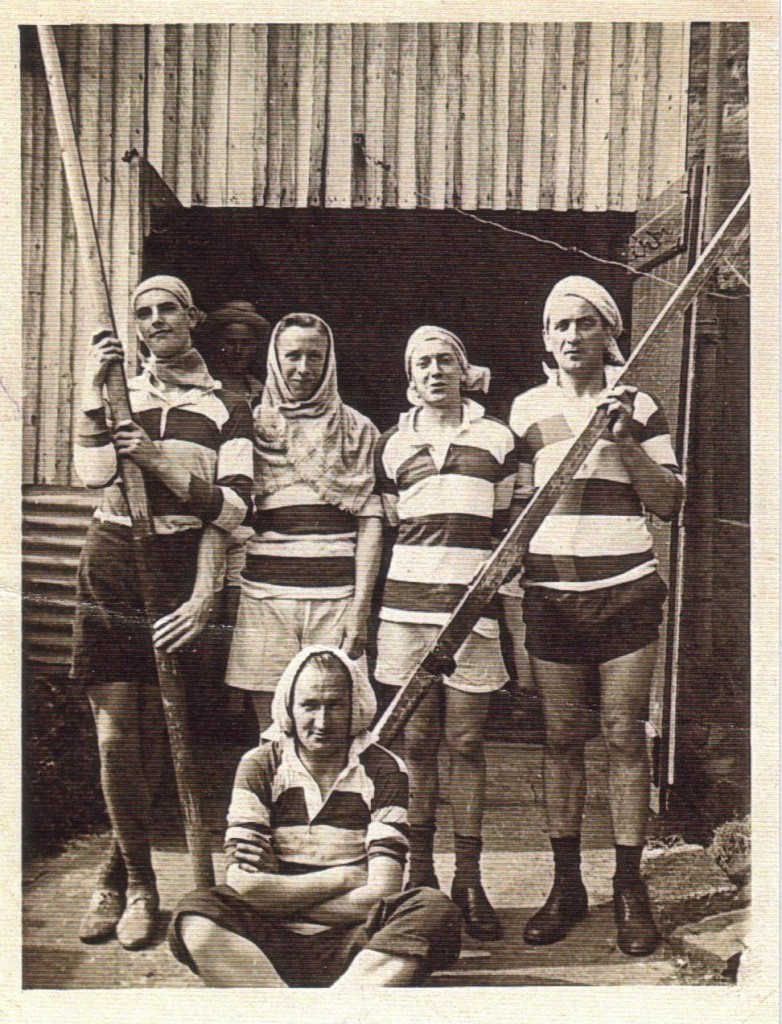

The Docklands have played a central part in Cork’s trading history and, being located in the heart of the city, feature greatly in the lives and memories of the local residents. The book is a visual record of the dockers and stevedores who work the wharfs, the business operators, and the sporting clubs, such as the rowers and the American football players, which use the waterways and fields for recreation.