The following is an article written by Mr. Vincent O’Sullivan, former Principal of St. Patricks School and included in a publication celebrating the 50th. anniversary (1987) of the Schools opening. (Source: http://www.stpatrickscork.com/stpatricksschool.html )

St. Patrick’s School, the Founding and Early Years.

Today we take for granted the availability of primary education for all, but up to the early part of the last century schools were few and far between. However, even before the passing of the National Education Act of 1831, primary schooling was being provided in the St. Patrick’s Area. On October 8th. 1822, Brickfields Male and Female Free School began operating in the upper storey of two adjoining houses in Lower Glanmire Road. A yearly rent of £11.13.6 was paid to the owners who continued to live in the ground floors. The income required to run the school was provided from the proceeds of an annual charity sermon, which averaged £15, and from subscriptions, which averaged £10 annually. Tuition was provided free of charge.

In October 1833, the school was taken in under the National Education system, Rev. James Daly, who was senior curate at the Cathedral Parish, became manager of the school, Rt. Rev. John Murphy, Bishop of Cork, patron and Mr. Paul McSwiney, King St., (now MacCurtain St.) became treasurer. By this time there were 60 boys and 40 girls attending the school although the potential for growth was noted by the commissioners for National Education. Thomas Riordan taught the boys for an annual salary of £20 while Ellen Crosby had to be content with £13 per annum for teaching the girls. However, the Brickfields School ceased to exist in 1840. It was described by James Sheridan, Superintendant of National Schools, as ‘very badly conducted and capable of accommodating only a few pupils.’

St. Patrick’s School opened to pupils for the first time on 13th September 1841. It’s location at St. Luke’s Cross was described by it’s first manager, Rev. Patrick William Coffey, as ‘the most central of St. Patrick’s district and approachable by six roads which meet at this point.’ Fr. Coffey, in his letter of 20th. September 1841, applying for aid towards the payment of teachers’ saleries and supply of books, informed the Commissioners of National Education that ‘the educational wants of the poor in the district of St. Patrick’s in the parishes of S.S. Mary and Anne Shandon in the eastern suburbs of the city of Cork induced the clergy and laity of the parishes to confer on this important subject two years back.’ The Brickfields School, he told them, had been found ‘inadequate and incommodious for the growing numbers of the poor.’ The site for St. Patrick’s School he described as having 100 feet frontage and 150 feet depth.

He added that ‘a substantial schoolhouse’ had been built by the contributions of the local clergy and laity. He had the satisfaction, he said ‘of numbering several Protestants benefactors’ among the contributers. The school building he describes as containing ‘for males the lower room running along the entire length of the building, and it’s dimensions are 45 feet in length, 30 feet in width and 17 feet in height, each side being lighted by four metal sashed windows and the room ventilated from the top. An upper room for females corresponds to the lower in dimensions and arrangements, and is accessible (by reason of the inclined site of the ground) from the road in the opposite direction by which the male or lower school is entered’. The male school was furnished with ’20 new forms with fixed desks, ten feet long each, and the female school with 15 new forms with fixed desks of like length’. Each room had ‘one large frame 8 feet high supporting a thin blackboard four feet square, hung on weighty pulleys and used for public diagrams, one raised bench containing a desk’, lockers for the teachers and also for holding the school register ‘under key’. There were two grates ‘in which fires are kept in the winter’. The patrons, he said, were anxious to open the school immediately, and therefore had borrowed one hundred pounds from the bank ‘to carry out the original work of surrounding the school ground with a wall and to furnish the schools with benches and forms.

The Commissioners were informed that ‘after public notice, Mr Michael O’Mahony, aged 27 years (who had taught at Brickfield School) was appointed to teach the male school and Mrs. Ellen Kennedy, aged 30 years, to teach the female school’. There was an average of 300 pupils enrolled in the schools during the early months, 174 boys and 126 girls. The scholars paid 1d per month although, on the manager’s instructions, approximately 100 pupils were admitted free of charge. School hours were from 9.30 a.m. to 3.30 p.m. and ‘a portion of Monday for religious instruction’. Religious instruction was also provided on Sunday by Fr. Coffey or another priest if he was not available. The school according to Fr. Coffey, was ‘open to every visitor who shall be at liberty to enter remarks on the book kept for the purpose, provided the presence of visitors interferes not with the order or application of children or teachers’. The manager visited the school frequently, ‘some weeks thrice, at other periods once a fortnight, never I believe less’.

Michael O’Mahony did not remain long in the position for by the time James Sheridan, Superintendant of National Schools, visited on March 1st. 1842, Danial Sheehan (aged 19 years) was the boys’ teacher. And so as Ireland moved towards the Great Famine, St. Patrick’s School was firmly established. The school manager and the driving force behind it’s founding, Fr. Coffey, who had been appointed first administrator of St. Patrick’s Chapel of Ease in 1836 did not survive long. He died (aged 42 years) on June 17th. 1847, the blackest year of the Famine, of a malignant typhus fever contracted while ‘attending the dying bed of a patient’. There is a plaque to his memory in the Church ‘erected in gratitude and affection by the parishioners of St. Patrick’s to the memory of their beloved pastor, friend and guide.’

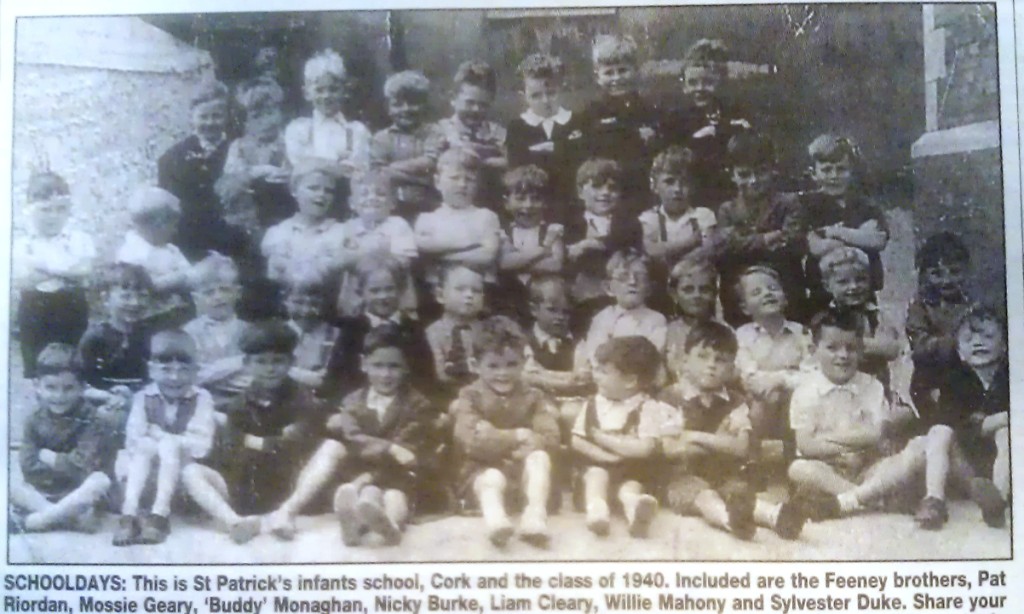

For the next twenty years, despite the depression of the Famine and its aftermath, the school developed and expanded. By 1863 extra building and reorganisation became necessary. St. Patrick’s Infants’ School was opened on June 1st. of that year in a schoolroom adjoining the male and female school. It was erected with funds left by the late J. Murphy Esq. of Clifton, Montenotte. Bridget Conner (18 years), who had been assistant teacher in Sunday’s Well, was appointed as first teacher in charge. There were 34 boys and 51 girls enrolled on opening day, the pupils had come mainly from the existing Boys’ and Girls’ Schools. Numbers increased quite dramatically for within ten years there were 300 pupils attending the Infants’ School alone.

The need for adult education must have been felt in the district at the time for, on February 3rd 1886, on application of Rev. John Canon Browne (school manager), an evening school was opened in St. Patrick’s Male School. It was in operation from Monday to Thursday of each week from 7.00 p.m. to 9.00 p.m. during the entire year. It was conducted by Thaddeus O’Conner who was also master of the day school. Reading, writing, arithmetric and geometry were taught. The National School books were in use as well as the Christian Brothers’ Arithmetric. Seventy seven names were on the books (all male) of whom thirty were present when the school was visited by J. Sillic, District Inspector of the Board of Education. He recommended the application, commenting that the evening school was required in the locality and noted that the schoolroom had been lit by gas. Four of the students enrolled were also pupils of the day school, fourteen of them were adults average of nineteen and a half years of age, all of them were employed in the locality. Their occupations are described as* shipbuilding, boilermaking, rivetmaking and carpentry.

The evening school has not survived but otherwise, apart from a change in location, the Infants’ Girls and Boys’ Schools continue to this day.